Because of COVID, almost no foreigners have been allowed in China for two years. While exceptions have been made for business and health professionals (plus of course Winter Olympians), the government still requires a lengthy quarantine period of 14 to 21 days upon landing. Most people have understandably chosen to conduct their business on Zoom or WeChat for the time being. And although there have been indications in recent months that China is ready to loosen its infamous Zero-COVID policy, a recent spike in cases likely means that the Middle Kingdom will remain mostly closed for the foreseeable future.

Whenever China does reopen its borders, foreigners are likely to be exposed to an entirely new country than the one they had become accustomed to. Anyone who has traveled to China with some regularity over the past decade knows how rapidly things change there. As just one example, within the span of a few years it went from being a functionally cash-only society to a cashfree one. I expect the biggest shock in the coming years will be the absence of English and the expectation that visitors know at least elementary Chinese.

After decades of encouraging students to learn English to prepare them for success in international business, President Xi Jinping restricted after-school English language tutoring last summer. The city of Shanghai banned any exam that tests students’ English skills. Viewed favorably, these “reforms” could be seen as an attempt to instill in Chinese citizens pride in their own language. No nationalist worth his salt wants to lead a country in which it is taken as a given that the people have to learn a different country’s language in order to have financial success.

But the anti-English policies do not end there. In the run-up to the Olympics, the government actually took down English subway signs and replaced them with pinyin. This was a drastic move, since it is directed not at China’s own citizens but to people visiting from other countries. And not just from America but from any other country where the cultural imperialism of the U.S. has led to much greater familiarity with English than with Chinese. One time when we were in Macau, we saw a Korean couple approach a bus driver to inquire about his route. They asked their question in English, and the bus driver answered in English. At their closest points, South Korea is about 300 miles from mainland China. It is over 3,000 miles away from Alaska, by far the closest U.S. state. Yet, in the 21st century, the lingua franca between these Asian civilizations has its roots on a tiny island in the North Atlantic they didn’t even know existed a few hundred years ago.

The sign policy is designed to change that. Expecting Westerners to learn Chinese characters may be a big ask. But if travelers to Mexico know elementary phrases like “Dónde está el baño?” perhaps they should also know how to say “xǐshǒujiān zài nǎlǐ.” In this scenario, the Chinese would have to be lenient on successful pronunciation of the tones. Judging by Chinese social media, where “netizens” relentlessly mock the “horrible Chinese” of pretty much every Westerner that dares speak it (ask John Cena), I am not sure this is particularly likely.

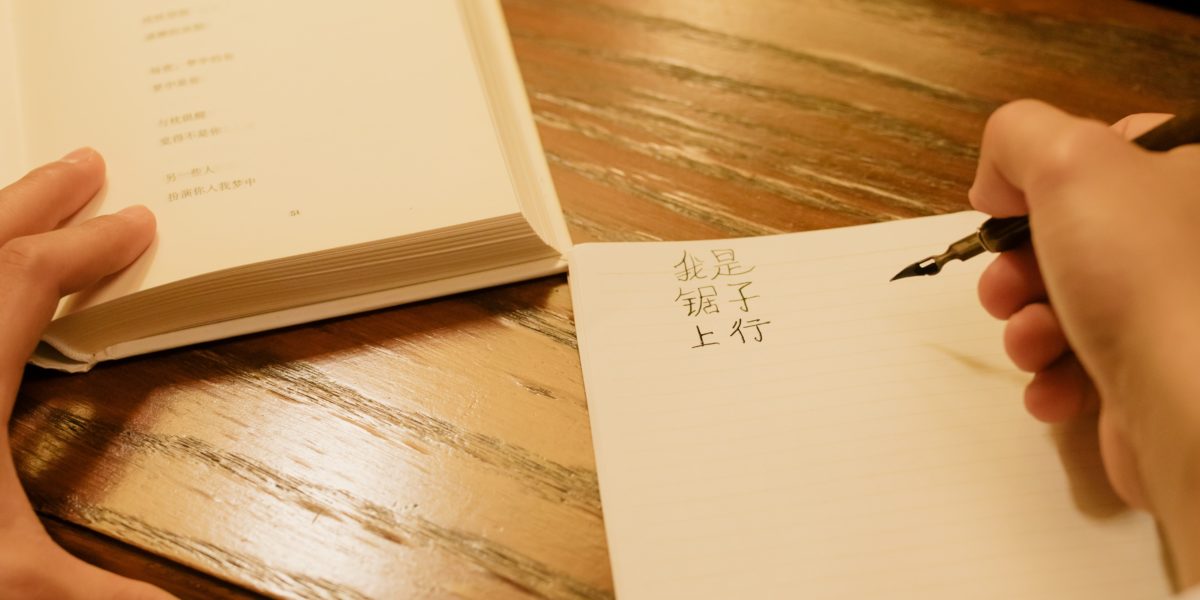

The upshot of all this is that if you are doing business in China, it is time to start learning some Chinese. There is a theory in business that states that as long as you are conducting negotiations in your native tongue, you have the upper hand. By all means, this may be true. And at any rate it is going to take you years before your Chinese is good enough to be able to do that with any degree of sophistication in their language. But at some point it may be necessary. You need to be prepared. The unipolar world is currently in the process of unraveling, and, paradoxically, as China continues to grow as a world power, its people are going to become less and less competent in English. This presents its own share of opportunities, as they are going to need more help marketing their products to the English-speaking world. It also presents its own challenges, and those who have had successful business dealings in China without knowing a word of Mandarin should not let it catch them by surprise.